ModPo update: 1) help with essays; 2) week 6 coming; 3) new video clip

We have very nearly reached our goal of providing every ModPo essayist at least four responses to their essay! I have found just a few essays—for instance, THIS one and THIS one and THIS one—that have received fewer than four. Please click the links in the previous sentence and respond to those essayists! And in then please look at the essays posted HERE to find others that could use further comments. Thank you. Together we are proving that qualitative crowdsourcing really works! And that “peer reviewing” does not necessary diminish the quality of critical response to poetic interpretation—but in fact, arguably, enhances it by varying and diversifying it. (That’s certainly my position on the matter!)

This weekend I’ll write you about week 6—which begins on Sunday. Below I’ve copied the headnote to week 6. And HERE, for those wanting a sneak preview, is my audio introduction.

HERE is a new video clip—4 minutes in which we discuss Stein as a conversationalist (at the Montreal webcast).

Get ready for the Beats. More soon!

Meantime, I send you my many thanks for participating, in whatever way you can, in the extended ModPo community,

—Al

HEADNOTE TO WEEK 6 in the MAIN SYLLABUS:

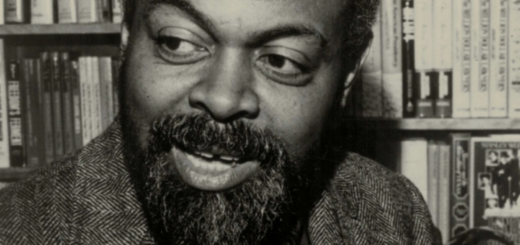

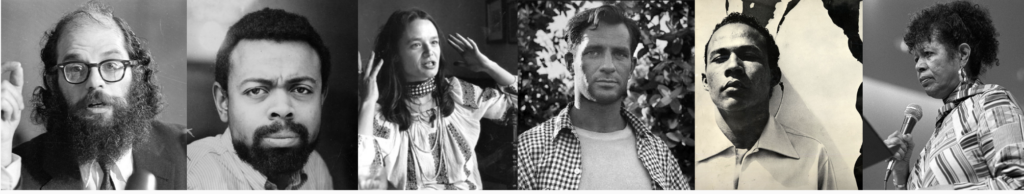

The so-called “New American Poetry” that emerged in the late 1940s and 1950s went in many directions; some trends, styles, and approaches overlapped, while some were (or seemed to be) more distinct and separable than others. The “Beat” poets were a fairly distinct community of writers, making it easier than it would be otherwise to study as a coherent movement their ecstatic, antic, apparently anti-poetic break with official verse culture. Our approach, in just one week, looks at two “classic” Beats (Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac) and then quickly moves off to adjacent figures. Robert Creeley was not a Beat poet, but his most famous poem engages poetic, psychological, and social matters with which Ginsberg, Kerouac, and the others were obsessed. Anne Waldman is an “outrider” poet and is more closely associated with the second generation of “New York School” poets (see chapter 8), but she was a dear friend of Ginsberg and learned a great deal from his political pedagogy. Amiri Baraka, as Leroi Jones, was a Beat poet for a few years and then broke away. The poem by Baraka that we study here gives us a chance to look back on Countee Cullen’s traditionally formal poetic response to racist hatred. The prose-poem/manifesto by Baraka on how poets (should) sound extends a theme already important to this chapter: the primacy of sound (or music) as a form of freedom from linguistic convention. Jayne Cortez gives us a perfect example of this and permits us to suggest connections among the Beat aesthetic, Black Arts, the influences of jazz, and the emergence of “spoken word” performance. Our focus on Jack Kerouac in chapter 7 is a little unusual — he, of course, is known more as a novelist than a poet. But his “babble flow” has been a significant influence on contemporary poets, more than his narrative fictional stance as psycho-social itinerant. We will have occasion, then, to examine and question Kerouac’s — and implicitly, Ginsberg’s — claim to be writing naturally spontaneous language. Our chapter 9 poets for the most part doubt such a claim.